“Unlike refugees, migrants can return to their homes”

“Migrants that fled the effects of climate change did so not out of choice but out of the need to escape conditions that could not provide for even the most fundamental of their rights.” (Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights)

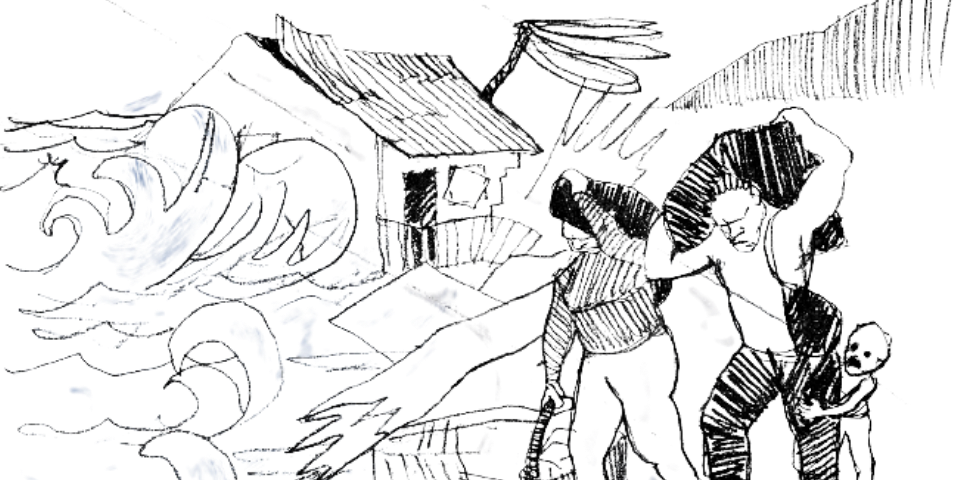

There were 18.8 million new displacements in 2017 alone due to natural disasters. While the intensification of weather-related natural disasters may most clearly connect climate change as a driver of migration, slow onset impacts, including “sea level rise, salinization, drought, and desertification” also have an adverse effect on human rights and may compel individuals to relocate, either within their country of residence or abroad.

Central to the need for international action to combat climate change, and to support and protect climate migrants, is the fact that States that contribute the least to climate change are often most impacted by its effects. For example, Africa has been and will continue to be disproportionately impacted by climate change. The continent is “expected to warm up to 1.5 times faster than the global average”, even though it accounts for only 4% of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions. More broadly, the World Bank estimates that by 2050 more than 143 million people could become internal climate migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America if no action is taken.

Reality from the ground

Climate change impacts on residents of Kiribati

FI has addressed the issue of climate migration in its work, including in its 2014 and 2020 joint submissions for the Universal Periodic Review of Kiribati.[i] The 2014 submission noted the impact of rising sea-levels and an increase in storm surges on the people of Kiribati, which leaves individuals “exposed to sudden inundation and drowning.”[ii] More generally, the impacts of climate change detailed in the submission included land shortages, decreases in agricultural harvests, and an increase in health issues. At the time, FI and partners noted the necessity of determining “how to deal with a nation whose land is increasingly uninhabitable.”[iii]

Nearly six years later, the international community, while still dealing with this question, has moved towards greater recognition and protection of climate ‘refugees’ or migrants.

In January 2020, the UN Human Rights Committee reviewed a communication from a national of the Republic of Kiribati, who was challenging the rejection of his application for refugee status and subsequent deportation from New Zealand. The individual had asserted that climate change and rising sea levels forced him and his family to migrate and, by rejecting his application, New Zealand violated his right to life under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[iv]

While the Committee accepted that rising sea levels would “likely render the Republic of Kiribati uninhabitable,” it noted:

“the timeframe of 10 to 15 years, as suggested by the author, could allow for intervening acts by the Republic of Kiribati, with the assistance of the international community, to take affirmative measures to protect and, where necessary, relocate its population.”[v]

The Committee did recognize the effects of climate change, but in this particular situation, found that because of this timeframe and concurrent steps taken by the Government of Kiribati, the individual did not face “a risk of an imminent, or likely, risk of arbitrary deprivation of life upon return to Kiribati.”[vi] Although the petitioner himself was not granted refugee status, the decision ultimately leaves the door open for others seeking protection from the effects of climate change.

Years prior to the decision, the President of Kiribati had already emphasized that its inhabitants did not want to become refugees and instead coined the concept of “migration with dignity” where citizens could be prepared and “make informed future choices” on the reality of the habitability of their nation.[vii]

_______________

[i] 76 Joint Stakeholders’ Submission on: The Human Rights Situations in Kiribati, Universal Periodic Review of the Republic of Kiribati, 35th Session, (20-31 January 2020), Franciscans International, et al, available at https://franciscansinternational. org/fileadmin/media/2020/UN_Sessions/HRC43/UPR35_Kiribati. pdf

[ii] Joint Stakeholders’ Submission on: The Human Rights Situations in Kiribati, Universal Periodic Review of the Republic of Kiribati, 21st Session (October-November 2014), Franciscans International, et al, available at http://www.upr-info.org/sites/ default/files/document/kiribati/session_21_-_january_2015/ js1_-_joint_submission_1.pdf

[iii]Id. at para

[iv]Views adopted by the Committee under article 5 (4) of the Optional Protocol, concerning communication No. 2728/2016, Human Rights Committee, 7 January 2020, CCPR/C/127/D/2728/2016, paras. 1.1 – 2.1, available at https:// undocs.org/CCPR/C/127/D/2728/2016

[v]Id. at para. 9.12

[vi] Id. at para. 4

[vii]Statement by He Te Beretitenti (President) of the Republic of Kiribati, His Excellency Anote Tong, on the occasion of the Panel Dialogue on Climate Change and Human Rights, 6 March 2015.

Climate Change and the Right to Life

State Obligations:

Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights affirms the right to life. The UN Human Rights Committee notes:

“Environmental degradation, climate change and unsustainable development constitute some of the most pressing and serious threats to the ability of present and future generations to enjoy the right to life […] Implementation of the obligation to respect and ensure the right to life, and in particular life with dignity, depends, inter alia, on measures taken by States parties to preserve the environment and protect it against harm, pollution and climate change caused by public and private actors.”[i]

As mentioned before, Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights affirms the right to an adequate standard of living, which includes adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has affirmed that the right should be “seen as the right to live somewhere in security, peace and dignity.”[ii] Adequacy is determined in part by climatic, ecological, and other factors.

_____________

[i] General comment No. 36 (2018) on article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, on the right to life, 30 October 2018, CCPR/C/GC/36, para. 62, available at https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CCPR/Shared%20 Documents/1_Global/CCPR_C_GC_36_8785_E.pdf

[ii] CESCR General Comment No. 4: The Right to Adequate Housing (Art. 11 (1) of the Covenant), Adopted at the Sixth Session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, on 13 December 1991 (Contained in Document E/1992/23), para. 7, available at https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/ Treaties/CESCR/Shared%20Documents/1_Global/INT_CESCR_ GEC_4759_E.doc

Global Compact on Migration

Objective 2 (h): “Strengthen joint analysis and sharing of information to better map, understand, predict and address migration movements, such as those that may result from sudden-onset and slow-onset natural disasters, the adverse effects of climate change, environmental degradation, as well as other precarious situations, while ensuring effective respect for and protection and fulfilment of the human rights of all migrants”

Objective 5(h): “Cooperate to identify, develop and strengthen solutions for migrants compelled to leave their countries of origin owing to slow-onset natural disasters, the adverse effects of climate change, and environmental degradation, such as desertification, land degradation, drought and sea level rise, including by devising planned relocation and visa options, in cases where adaptation in or return to their country of origin is not possible”

Franciscans International, the NGO of the Franciscan Family to the United Nations, has prepared this material. The publication presented in this post is an extract from the document Breaking down the Walls, “Myth 4: Unlike refugees, migrants can return to their homes” you can do it here ↓